World Bank Raises Growth to 2.7%, Highlights Resilient Risks

When I first studied the World Bank’s latest global outlook, I didn’t react with alarm; I reacted with curiosity. On the surface, the numbers seemed calm, even mildly reassuring. Growth forecasts had been nudged slightly upward, and the global economy appeared to be holding steady despite geopolitical tensions, trade frictions, and lingering inflation pressures. But as I dug deeper into the World Bank report, the tone shifted. Beneath the stable surface, I saw signals that made me pause. Because here’s what stood out to me: stability does not automatically mean strength.

Table of Contents

ToggleThis article tries to make sense of exactly what the World Bank’s most recent perspective on the world actually tells us beyond a dash of numbers, why growth forecasts were raised, which countries are really guiding global expansion, where hidden risks have gathered and what all of this might mean for investors, policy makers and long-term economic stability.

A Forecast Upgrade That Isn’t as Positive as It Sounds

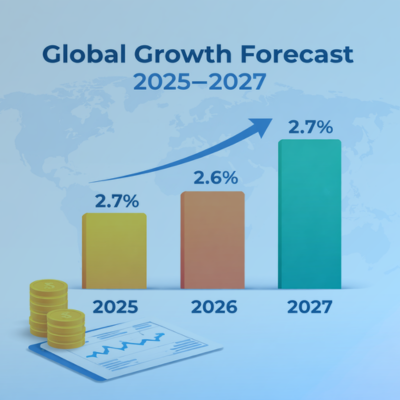

The World Bank now expects global GDP growth to stay around 2.7% in 2025, soften to 2.6% in 2026, and return to 2.7% in 2027. These projections were actually revised slightly higher compared to earlier estimates, which at first glance sounds encouraging.

But I’ve learned over time that upgrades only matter relative to expectations. If forecasts start low, even small upward revisions can appear optimistic. In reality, these numbers still point to a world economy growing at a modest, historically subdued pace.

This isn’t the kind of expansion that fuels rapid job creation, widespread income gains, or strong productivity growth. It’s the kind that keeps things moving, but slowly.

One Economy Is Doing Much of the Heavy Lifting

The biggest reason for the improved outlook is stronger-than-expected performance in advanced economies, especially the United States. Current projections suggest U.S. growth could reach roughly 2.1% in 2025 and 2.2% in 2026, both higher than earlier forecasts.

What struck me most is how much global momentum depends on that single economy. When one country contributes a large share of global growth, it becomes both a stabiliser and a risk factor. If it performs well, it supports worldwide demand. But if it slows unexpectedly, the shock spreads quickly.

That’s why I always pay close attention to U.S. macro data, not just on account of the domestic implications, but because it matters for the whole world, too.

Policy Timing Is Quietly Influencing Growth Trends

Another insight I found fascinating is how policy expectations are shaping economic activity. Businesses reportedly accelerated imports ahead of anticipated tariffs, which temporarily reduced net exports and slowed measured growth.

This is a reminder that economic data often reflects timing effects rather than fundamental shifts. When companies change behaviour to prepare for policy changes, the data can look weaker or stronger than reality.

Looking ahead, expected tax incentives could encourage business investment and consumer spending, potentially offsetting trade-related drag. If that happens, then any short-term growth may seem stronger than what lies beneath. For investors, that difference is everything. Short-term momentum is not necessarily long-term strength.

The Phrase I Can’t Stop Thinking About: ‘Low Growth, High Resilience’

One description in the World Bank report stuck with me: The global economy is transitioning into a low-growth, high-resilience era. That combination is unusual.

Historically, resilience and strong growth often went hand in hand. What we have today is something different: it can absorb shocks without collapsing, but finds it difficult to generate much in the way of acceleration.

In practical terms, this means:

- Markets may remain stable

- Crises may be less frequent

- But expansion could stay sluggish

To me, this suggests structural limits rather than temporary slowdowns.

The Most Concerning Projection: The Weakest Decade Since the 1960s

The part of the outlook that genuinely made me pause was its long-term warning. The World Bank suggests the 2020s could become the slowest decade for global growth since the 1960s.

That’s not just a statistic, it’s a structural signal.

Slow global growth over an entire decade can lead to:

- Persistent unemployment pressures

- Slower wage gains

- Higher debt stress

- Reduced fiscal flexibility for governments

For developing economies, the consequences are even more serious because their growth models depend heavily on expansion to improve living standards.

Emerging Markets Are Facing a Gradual Slowdown

Growth in emerging and developing economies is projected by the World Bank to slow to about 4.2% in 2025 and 4.0% in 2026. Those figures still exceed advanced-economy growth, but the direction matters more than the level. The trend is downward.

Even more revealing is that when China is excluded, growth across emerging economies is expected to hover around 3.7%, essentially flat year-to-year. That tells me many countries are struggling independently of China’s trajectory.

The obstacles they face are structural rather than cyclical:

- Weak private investment

- High sovereign debt

- Limited fiscal space

- Institutional inefficiencies

These aren’t problems central banks can solve with rate cuts. They require deep reforms.

China’s Transition Is Reshaping the Global Picture

China is still a major contributor to global expansion, with growth projected at around 4.9% in 2025 and 4.4% in 2026. Policy stimulus and export strength are helping in the short term.

But structurally, China is changing. Demographics are shifting, the property sector faces pressure, and its economy is transitioning from investment-driven growth to consumption-led expansion.

From my perspective, this transition is one of the defining macroeconomic stories of our time. The world spent decades adapting to China’s rapid rise. Now it must adapt to China’s gradual slowdown.

Global Growth Is Becoming Increasingly Concentrated

Another theme I observed is how lopsided global expansion has become. A smallish group of economies account for most growth, while many others drag behind. This concentration creates fragility.

When growth is broad-based, shocks in one place can be cushioned by strength elsewhere. But when growth relies on a specific set of engines, that strategy carries exaggerated risks.

It’s like diversification in investing: a diversified portfolio is less risky than one dominated by a single asset. This same logic holds for the international economy.

Also Read: European Stocks Begin Week On Low Note

Structural Reform Is the Real Long-Term Solution

One of the report’s strongest messages, and one with which I fully agree, is that monetary policy alone cannot deliver sustainable growth.

Lower interest rates can stimulate borrowing and spending temporarily. They can’t, however, solve the underlying productivity issues, governance failures or lack of infrastructure. Sustainable growth requires structural changes, including the need for:

- Improving education systems

- Expanding access to finance

- Strengthening institutions

- Investing in infrastructure

They are nothing more than incremental, politically fraught reforms. Yet without them, the growth ceilings are low.

My Personal Takeaway as an Observer of Global Trends

After analysing the data and thinking through its implications, here’s where I stand: The global economy is not in crisis, but it’s also not in an especially strong expansion.

We’re entering a period that may feel stable on the surface yet constrained underneath. Markets could remain resilient, but long-term growth potential appears limited unless major structural changes occur.

What concerns me most is that slow trends rarely trigger headlines. Investors prioritise large and dramatic news like crashes, rate hikes, and crises while slower movements occur silently behind the scenes. But, these gradual changes often determine the future far more than any one jolt.

Final Thoughts

What fascinates me most about today’s global economy is its paradox. We’re living in an era when systems are great at absorbing shocks but bad at building momentum. That mix implies a new economic phase, but not one of rapid expansion, rather one of cautious endurance.

For policymakers, the challenge is clear: transform resilience into dynamism.

And for investors, the lesson is as vital: don’t confuse stability with strength. In markets and economies, the greatest risk is usually the kind that takes its time emerging so that few take note.

Also Read: European Markets Set To Open Higher Amid Geopolitical Focus

Disclaimer

This article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, economic, or investment advice. Readers should conduct their own research or consult a qualified financial professional before making financial decisions.